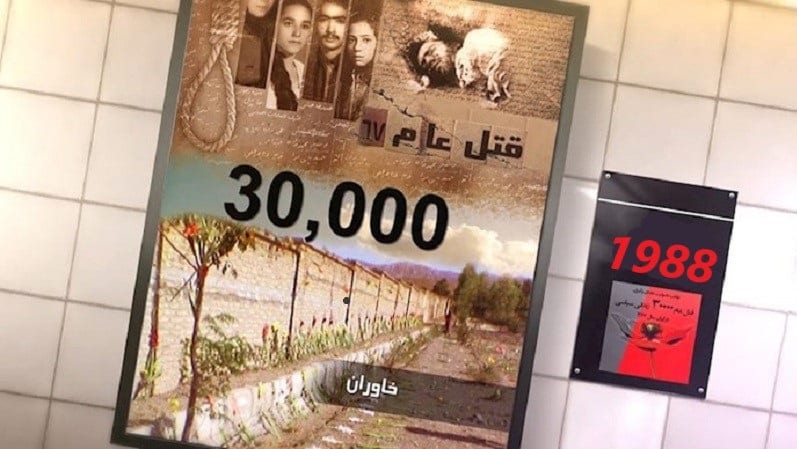

During the 1988 massacre, the Iranian regime killed an estimated 30,000 political dissidents over the course of several months, following a fatwa from then-Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini which described the regime’s opponents as waging war on God himself. The main target of that edict and the resulting systematic executions was the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran (PMOI/MEK), which was and remains the leading voice for a democratic alternative to the country’s theocratic dictatorship.

Recently, a number of current MEK members and relatives of the 1988 massacre’s victims joined in signing a letter to United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, which calls renewed attention to alleged crime against humanity. The letter also emphasized that Iranian authorities remain committed to a project of destroying evidence that might otherwise be uncovered by an international investigation into the massacre.

No such investigation has ever taken place, although various human rights groups have joined the MEK in demanding accountability over the years. In September 2020, seven UN human rights experts sent a letter to leading Iranian officials, communicating that demand to them and asking for the release of information that has been suppressed regarding the procedures behind the killings and the locations of mass graves where most of the victims are believed to be interred.

The Iranian regime’s response to that letter – or the lack thereof – only served to reaffirm its commitment to deflection and denial regarding the massacre and associated human rights abuses. In fact, the letter itself used these terms to describe regime behaviors that had been enabled by the UN’s initial failure to follow up on reports of an accelerating pace of executions in 1988. The human rights experts noted that references to the massacre made their way into that year’s resolution on Iran’s human rights record, but did not spur action from the Security Council, the High Commission on Human Rights, or any other relevant body.

Far from punishing or disavowing the major participants in the 1988 massacre, Tehran has repeatedly rewarded them with positions of greater power and influence within the regime. Presently, both the head of the judiciary and Iran’s Minister of Justice are individuals who previously served on the “death commissions” that determined which dissidents would be hanged on the charge of “enmity against God.”

Perhaps in recognition of this situation, the UN human rights experts clarified to Iranian authorities that if they did not take action on their own, the responsibility would fall to the international community. When their letter was published in December, it confirmed that no response had been received from Tehran and that a response would now be expected from the UN and its leading member states.

Amnesty International responded to that statement by calling it a “momentous breakthrough” and a prospective “turning point” in the campaign for accountability from the perpetrators of the massacre. That language was later cited in a resolution introduced to the US House of Resolution which expresses support for the democratic Resistance against the Iranian government, in the face of ongoing human rights violations and acts of terrorism.

Res. 118 also highlighted statements from Amnesty and the UN human rights experts which recognized that victims of the 1988 massacre were buried in mass graves in at least 32 Iranian cities. However, the MEK places that number at 36, including cities in which mass graves have already been concealed through a process of systematic destruction by regime authorities. Now, the letter from victims’ families calls renewed attention to that ongoing cover-up and urges the international community to take action to stop a development project targeting the mass grave at Iran’s Khavaran Cemetery.

“Previously, [the regime] destroyed or damaged the mass graves of the 1988 victims in Ahvaz, Tabriz, Mashhad, and elsewhere,” that letter says, underscoring the threat that such actions pose to the accuracy and completeness of any future investigation into the details of the massacre.

With this in mind, the letter also seeks to convey to Secretary General Guterres a sense of urgency regarding the need for such an investigation. After briefly recapping the circumstances of the 1988 massacre and the regime’s more than three-decade cover-up, the letter declared that “the Iranian public and all human rights defenders expect the United Nations, particularly the UN Security Council, to launch an investigation into the massacre of political prisoners and summon the perpetrators of this heinous crime before the International Court of Justice.”

It then concluded by urging Guterres himself, along with “the relevant bodies at the United Nations and international human rights organizations to prevent the regime from destroying the mass graves, eliminating the evidence of their crime, and inflicting psychological torture upon thousands of families of the victims throughout Iran.”